Across history the Phoenician alphabet stands out for a simple reason: it turned writing into an efficient tool for everyday life, trade, and diplomacy. This consonant‑based system traveled with merchants and seeded later traditions. Understanding how it worked, where it came from, and why its legacy endures helps you read claims critically and connect ancient evidence to modern alphabets.

What Is the Phoenician Alphabet?

The Phoenician alphabet is a consonantal writing system, or abjad, that uses twenty‑two letters written from right to left to record words. It encodes consonant sounds, leaves vowels largely implicit, and favors speed, clarity, and portability over decorative or pictorial signs.

The Phoenician alphabet records speech by mapping single consonant sounds to single letters, letting scribes write quickly on perishable materials or carve brief texts on stone and metal. Because vowels are typically unmarked, readers supplied them from context, proper names, and grammar. This design made short, practical messages possible for merchants and administrators who needed clear records in busy ports and markets.

Unlike syllabaries and logographic systems, which require many symbols or complex signs, the Phoenician alphabet uses a compact set of twenty‑two characters. Writers started at the right margin and moved left, shaping letter forms and spacing. Its popularity grew because it offered a portable, reliable tool rather than an elite art, and its letter‑sound principle remains central to everyday literacy.

Origins and Early Development

The script developed within a Northwest Semitic, or Canaanite, environment on the Levantine coast. Earlier consonantal systems, often called Proto‑Canaanite or Proto‑Sinaitic, supplied models and signs that Phoenician communities standardized, streamlined, and spread through their maritime networks.

By the late second millennium and early first millennium BCE, coastal city‑states like Byblos, Tyre, and Sidon used related consonant scripts for local needs. Over time, scribes settled on a stable set of forms and names, producing the recognizable twenty‑two‑letter system. This consolidation highlights practical choices rather than sudden invention.

Archaeology confirms the setting: short dedicatory texts, labels, and monumental inscriptions appear in port cities and their spheres of contact. Because these societies traded widely, their script moved easily, passing through crews, cargo, and contracts. The result is not a sudden invention, but a durable standard shaped by commerce and multilingual contact across the eastern Mediterranean.

Structure and Letter System

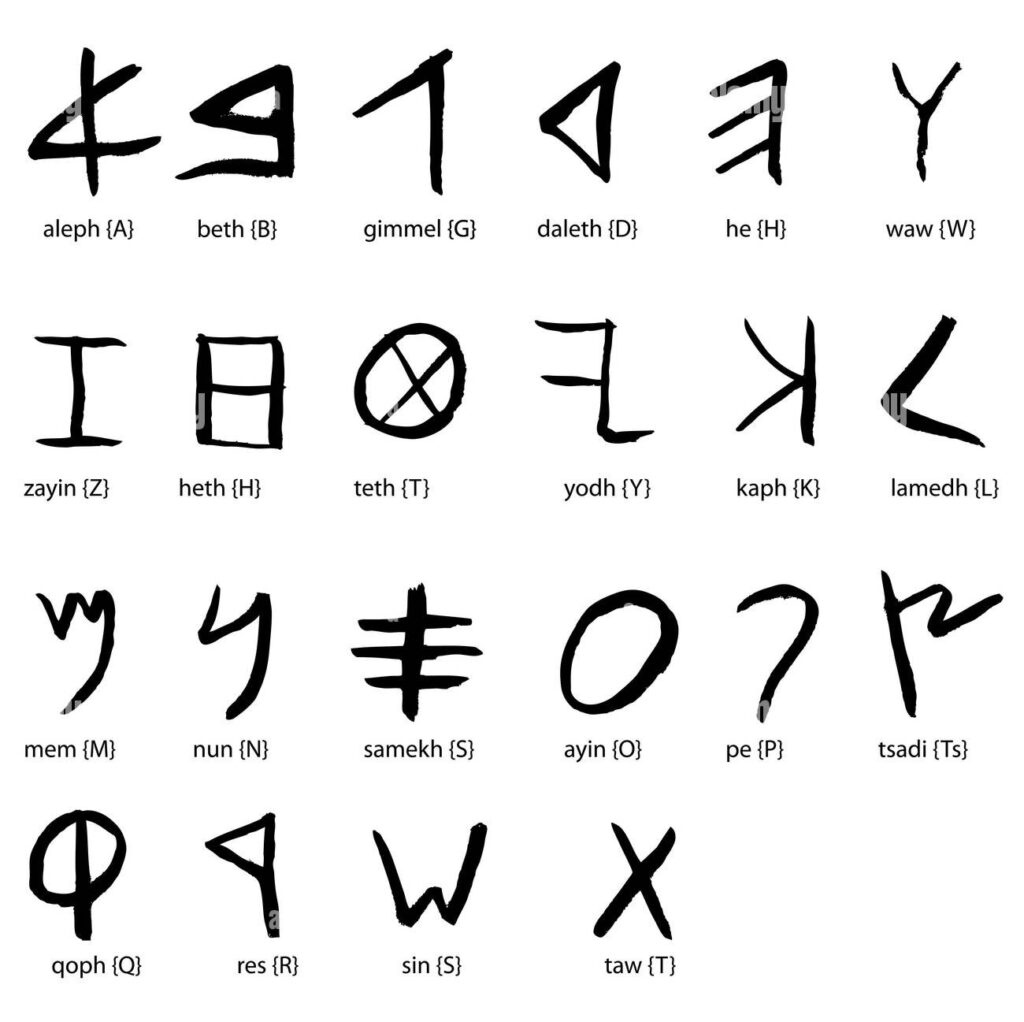

The alphabet consists of twenty‑two consonant letters, written right to left, with acrophonic names that hint at their original meanings. Vowels are not independent letters, so readers infer them from context or later scribal conventions in descendant scripts.

Each letter represents a single consonant phoneme, making the system efficient for Semitic languages whose word roots rely on consonant patterns. Letter names followed the acrophonic principle, where a letter’s name began with its sound, reinforcing learning and memory. Students connected everyday words to initial sounds instead of memorizing complex signs.

Because vowels were usually left unwritten, readers relied on morphology, syntax, and common phrases to supply missing sounds. For names or foreign terms, context and familiarity did most of the work. Later scripts developed ways to mark vowels more explicitly, but the Phoenician solution was adequate for the languages and purposes of its users, especially in trade and administration.

Compared with cuneiform tablets or Egyptian hieroglyphic and hieratic scripts, the Phoenician alphabet needed fewer signs and less training time. A merchant or clerk could learn the letters, track shipments, and label goods without mastering hundreds of characters. This practicality explains its adoption in ports and on ships across busy Mediterranean routes.

Spread, Transmission, and Evolution

Maritime trade carried the alphabet across the Mediterranean, where it encountered Greek communities, Etruscan cities, and later Roman culture. Each group adapted the letters to local needs, with Greeks assigning vowel values and setting a template for later European alphabets.

Phoenician traders linked Levantine cities to Cyprus, North Africa, Sicily, Sardinia, and Iberia. Along these routes, crews and artisans shared techniques and signs, letting the alphabet enter new environments naturally. Short inscriptions on pottery, metalwork, and stone accompanied goods and ceremonies, grounding the script in daily life rather than court spectacle.

Greek speakers borrowed letter shapes and names, but reassigned some consonant signs to serve as vowels, matching Greek phonology. This step produced a vowel‑bearing alphabet from a consonantal base. Etruscan and Roman writing followed, and through their institutions the Latin alphabet spread through law, administration, and education.

The alphabet’s legacy also runs through other Semitic traditions. Hebrew and Aramaic scripts developed parallel solutions for marking vowels and consonant nuances, often with diacritics. The shared heritage is visible in letter orders, shapes, and names, showing how a flexible consonant toolkit adapted to different languages, religions, and literary cultures over many centuries of use.

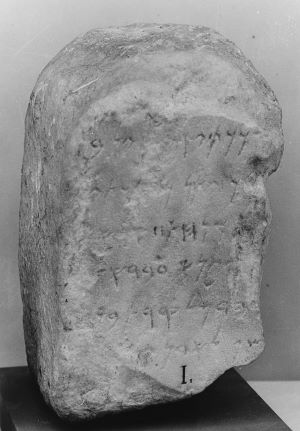

Key Artefacts and Inscriptions

Named artefacts provide firm anchors for readers and learners. They show when, where, and how the alphabet was used, and they illustrate contact with neighboring cultures that shaped transmission and adaptation across the Mediterranean world.

Inscriptions from Byblos and other Levantine sites display early letter shapes and formulaic phrases, often carved on stone or metal. These texts tend to be short, such as dedications to deities or labels identifying donors and objects. Even when fragmentary, they reveal conventions of line direction, letter spacing, and personal names that connect language to social identity and civic life.

The Pyrgi gold plates, discovered on the Tyrrhenian coast, illustrate a meeting point between Phoenician and Etruscan communities. Parallel texts demonstrate how ideas and practices crossed linguistic boundaries, enabling scholars to compare vocabulary and ritual expressions. Artefacts like these are invaluable because they fix cultural exchange to specific places, materials, and hands rather than abstract claims about influence.

Another touchstone is the Incirli stela, an inscription showing the reach of related Northwest Semitic writing in neighboring regions. It helps document the broader context in which the Phoenician alphabet circulated and interacted with local traditions. When studied together, such pieces let readers see transmission not as legend, but as repeatable patterns tied to trade routes and political alliances.

Timeline at a Glance

A concise timeline helps you situate developments without memorizing fine‑grained debates. These broad milestones track emergence, standardization, Greek adaptation, and later diffusion into familiar alphabets that dominate education and publishing today.

Late second millennium BCE: related consonant scripts flourish in the Levant; early monumental and dedicatory texts appear in port cities. Early first millennium BCE: a twenty‑two‑letter standard is widely visible; right‑to‑left writing and acrophonic naming stabilize. Later first millennium BCE: Greek adopts and adapts letters; Etruscan and Roman paths carry the system forward, culminating in the Latin alphabet’s rise.

How to Read Basic Phoenician Texts

You do not need to be a specialist to start recognizing features. With a letter chart, patience, and context clues, you can identify names, common words, and formulae that appear repeatedly in short inscriptions from coastal sites and trade outposts.

Step-by-Step Reading Method

- Identify direction:

- Phoenician lines are written from right to left. Start reading from the far right edge of the text.

- Recognize letter shapes:

- Each symbol stands for a single consonant. Vowels are not written, so you infer them using context or known word patterns.

- Spot familiar words:

- Many short inscriptions repeat personal names, verbs of offering, or divine references—terms such as mlk (“king”) or bʿl (“lord”).

- Fill in vowels mentally:

- When you see MLK, you read it as melek or malik, depending on context. This guesswork was normal for ancient readers.

- Understand formulaic structure:

- Most brief texts follow set phrases like “X, son of Y, made [this] for Z,” or “Offering to [deity].” Recognizing these patterns helps beginners translate confidently.

- Compare with known alphabets:

- Place Phoenician letters beside Hebrew or early Greek to see how forms evolved. Similar letters often carry the same basic sound.

Example 1: Basic Dedication Formula

Phoenician (transliterated):BN MLK L BʿL

Reading logic:

- BN → “son of”

- MLK → “king” or “Melek” (a name)

- L BʿL → “for Baal”

English meaning:

“Son of Melek for Baal.”

This formula would suit a short offering inscription on stone or metal.

Example 2: Simple Personal Statement

Phoenician (transliterated):ʾNK ʾBD MLK

Reading logic:

- ʾNK → “I”

- ʾBD → “servant”

- MLK → “the king”

English meaning:

“I am the servant of the king.”

This kind of phrase might appear on seals or personal belongings.

Common Misconceptions and Balanced Credit

Popular summaries often compress a complex story into a single claim about invention. A balanced view separates earlier Canaanite roots, Phoenician standardization and spread, and Greek vowel innovation, explaining why credit differs across audiences, textbooks, and scholarly traditions.

One frequent misconception says the Phoenicians invented the alphabet outright. A clearer statement is that they standardized a successful consonantal system and spread it widely through trade. Earlier Canaanite scripts pioneered the approach. Seeing standardization as the key achievement fits the evidence and honors the longer regional development.

Another misconception ignores the Greek contribution to vowel representation. Greek communities adopted the letter inventory but reassigned some signs to represent vowel sounds, meeting the phonological needs of their language. This upgrade shaped Etruscan, Roman, and later European writing. Many modern summaries highlight Phoenicians because Greco‑Roman histories framed the narrative, but balanced credit recognizes both transmission and transformation.

Lasting Impact on Modern Writing

The alphabet’s impact reaches far beyond coastal Levantine cities. Its principles of mapping sounds to letters, minimizing symbol counts, and favoring portability underlie many scripts that support education, trade, law, and technology across continents today.

The Latin alphabet, used for a wide range of European languages and global lingua francas, descends through Greek and Etruscan channels from this consonantal ancestor. That indirect lineage explains why basic letter orders and shapes feel familiar across cultures and centuries of schooling and publishing.

The deeper contribution is methodological. By focusing on phonemes rather than pictures or syllables, the Phoenician alphabet privileged analysis of sound and structure. This made literacy more accessible to non‑specialists and allowed writing to scale with commerce and bureaucracy. The results are visible wherever compact scripts enable quick notes, labels, and correspondence without years of scribal schooling.

FAQs

These brief questions address common user goals, reflecting topics already covered above. Answers restate key points in plain terms, helping you recall definitions, differences, and historical sequences without searching beyond this page for basic clarification.

Did the Phoenicians invent the alphabet?

The safer answer is that they standardized and spread a successful consonantal script across the Mediterranean. Earlier Canaanite systems pioneered the approach, and Greeks later adapted letters to represent vowels, shaping the vowel‑bearing alphabets familiar in Europe.

How many letters are in the Phoenician alphabet, and which direction does it read?

The script has twenty‑two letters representing consonant sounds, and it reads from right to left. This compact inventory supports quick writing and practical labeling, a key reason it suited merchants and administrators.

What makes the Phoenician alphabet different from syllabaries or hieroglyphs?

It uses a small set of signs, each linked to a single consonant sound. That design reduces memorization, speeds training, and helps ordinary users handle records, compared with systems needing hundreds of complex symbols or pictorial signs.

How did Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans use the script?

Greeks borrowed letter shapes and names, then repurposed some consonant signs as vowels to fit Greek phonology. Etruscans and Romans inherited and adapted those solutions, eventually producing the Latin alphabet used widely for law, religion, science, and education.

Why do many books still give the Phoenicians most of the credit?

Because trade brought Phoenician letters directly to Greek communities, and Greco‑Roman histories shaped later teaching. That perspective highlights Phoenician transmission, even while acknowledging earlier Canaanite roots and Greek innovation with vowel representation.

Where can beginners start if they want to read an inscription?

Learn the twenty‑two letters, practice right‑to‑left reading, and study common formulas found in dedications and labels. Use clear photographs and reliable transcriptions, and rely on context to supply vowels when the script leaves them unmarked.